Reviews

DOUG MEYER

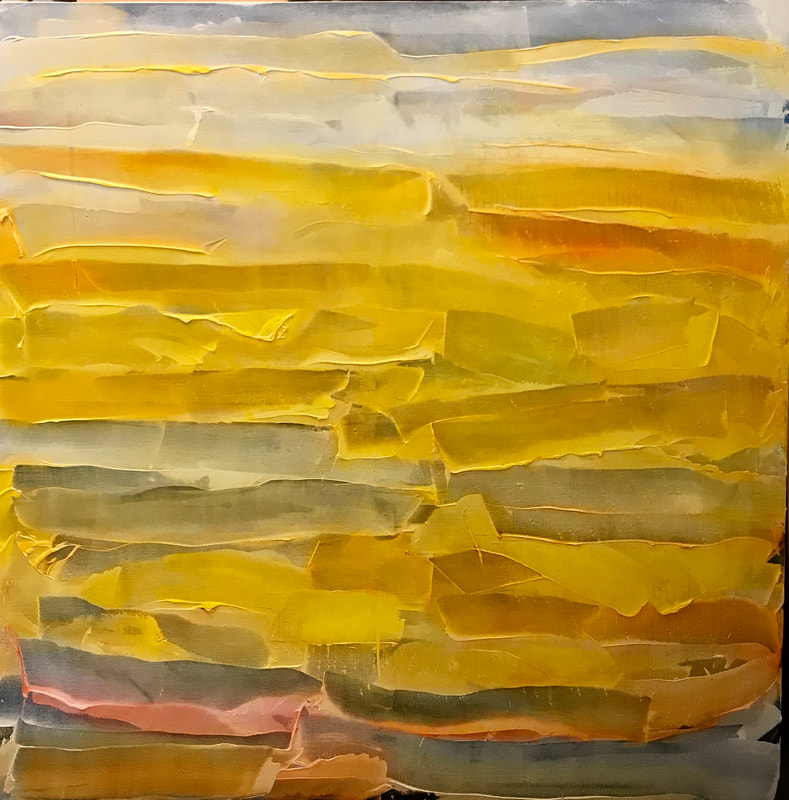

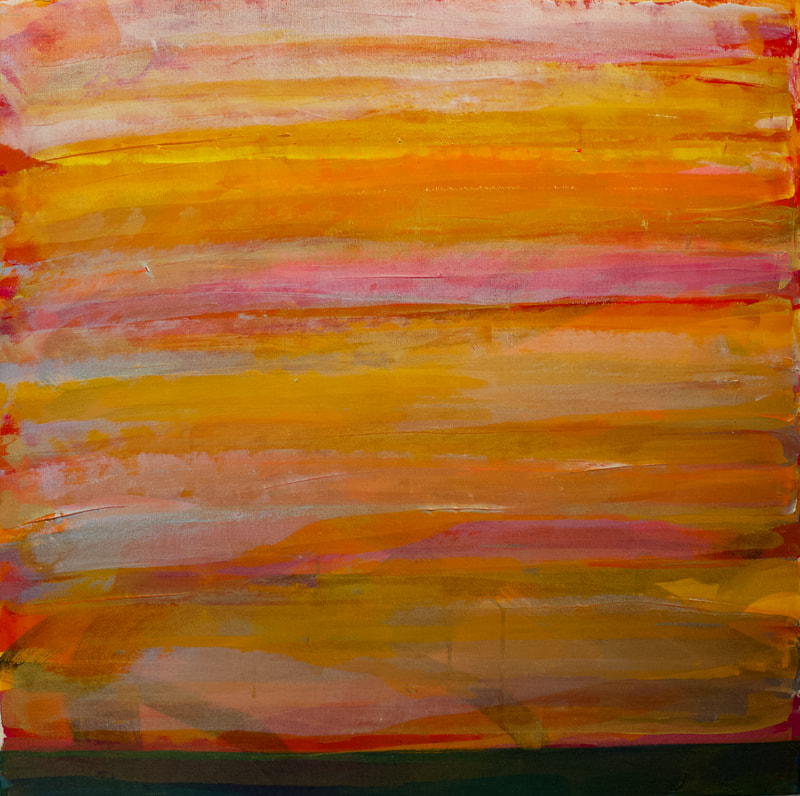

I think Van Tuinen’s paintings have a way of telling us how to find and unlock that quality of light and color inherent in nature. It is like staring into early evenings dark shadows to see pure violet, or waking up and find everything golden in the light of dawn. |

|

The word “ radiance” suggested equal parts science and spiritually. Debra Van Tuinen’s paintings possess radiance. They bask in the reflected light of a physical universe beyond the picture plane. They emit waves of spectral energy producing a sensory-loaded retinal response. They glow.

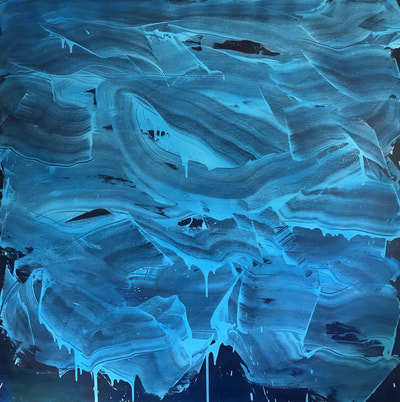

These paintings acknowledge the unsolvable mysteries of the universe, the intangibility of nature’s experience. So why do we feel such a sense of place in Van Tuinen’s amorphous atmospheres? There is such a mystery in a process that reduces the panoramic to a relatively small scale yet retains its sense of vastness. Like a Montana sky we experience these works as expansive, because of their radiance. The luminous color fields swell outwards to push beyond the physical constraints of their formats. The implied illusion is that of a boundless space in which human scale is rendered irrelevant, where physical substance dissolves into pure sensation. It is necessary to disengage with the temporal and the analytical to enter into these world apart. Only then do we find ourselves being lifted upward and outward by the forces that drive these paintings. It is clear from looking at these works that they record Van Tuinen’s experiences with nature and from these experiences she has gathered up a chromatic response to the color and light that is found in the earth and sky. They allude to forms beyond the picture plane but with the picture there exists mostly mist and vapor, refraction and reflection. She solicits a separation of the spirit from the body, extracting the timeless from the transitory, all the while getting closer to the experiences that have inspired her. This experiment, visionary world is the realm of the painterly romanticism, as seen in the same non-linear sorts of compositions envisioned by Turner two centuries ago, and Monet a hundred years later. They both sought to embody light, expressing it through a highly attenuated chromaticism and the use of the brush which subverted literal illusion. Mark Rothko’s atmospheric abstractions of the 1950’s and 60’s are a modern precedent for Van Tuinen’s ephemeral approach, emphasizing the sensory experience of color and light, de-materializing form. Rothko too, is a painter of the American landscape, that place of expanse and light that defines a kind of New World romanticism. In the Pacific Northwest where Van Tuinen resides nature asserts itself strongly in the ever present deep green forests, turbulent skies, and cold rushing streams. The Western landscape as subject matter can be said to represent an embodiment of a kind of romantic expressionism in its stunning beauty on a grand scale, evidence of the powerful transcendent spirit of the creative force behind all things. In the romantic/symbolist canon the veracity of the pure feeling seeks to triumph over the “treason of images”. Debra Van Tuinen manages to uphold this transition while embracing an optimism offered up by the nature in its eternity. Over time, the forms of the earth change, but there is constant in the forces of nature, a continuum of wind, water and sun the provide the visual definition of this planet. Van Tuinen’s disembodied forces of nature contain apparitions of shifting cloud-like ephemera in colors that convey depth through overlapping colors, the shapes in front being brighter spectral hues, seemingly hovering in front of darker, more neutral colors. The edges are often dark, creating centralized patches of radiance like seeing the sky be between the trees reflected in the water. |

In Van Tuinen’s vertical formats the openness of the square paintings gives way to a more restricted view, down a canyon or following the a river. Recent works have alluded to the panorama of the Pacific shoreline. Multiple panels poetically express the changing nuances of light that inform her colors so brilliantly. We have all seen the bright flashes of color that nature presents in fleeting displays, but Van Tuinen’s paintings channel the flashes into surging, swirling fields that seem to grow larger before our eyes, hovering before us in a full display of the most sensual color that can be wrought from the earth. The transparent layers of color are made almost tangible and definitely tactile by the lush surfaces that Van Tuinen has fashioned.

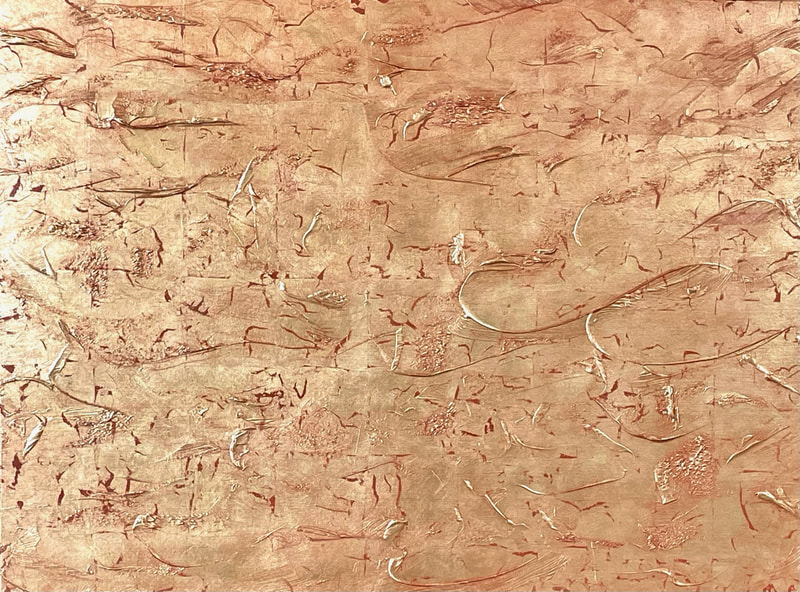

The use of the encaustic technique give the surfaces of Debra Van Tuinen’s paintings a soft, matte translucency that invests a sense of atmosphere into her overlapping color fields. One can literally see into the paintings and yet there is a physical layering of oil and wax that readers a luscious sculptural facility. Van Tuinen works not the surfaces with a variety of implements and draws into the waxy surfaces with oil stick in the process marrying the under layers to the “skin” of the painting. The process that Debra Van Tuinen uses are both ancient and innovative, as she continues to refine her craft to express her vision. She credits her five months in Japan back in 1977 with a leap forward in her technical skills. It was at this time she began a transition from the process of intaglio printmaking into painting, eventually creating an encaustic process studio that enables her to make the best use of this technically demanding yet sensual medium. As I look at a reproduction of Debra’s painting from 2001 entitled Morning Peace 1, I am reminded of an Elliot Porter photograph of water reflecting fall colors and a brilliant blue autumn sky. What we are looking at is humble puddle of water in a dry canyon, a stark place where one must look hard to find the intensity of the color that is hidden there. I think Van Tuinen’s paintings have a way of telling us how to find and unlock that quality of light and color inherent in nature. It is like staring into early evenings dark shadows to see pure violet, or waking up and find everything golden in the light of dawn. Perhaps it is the capturing of that quality of light, that sort of radiance, in Debra’Van Tuinen’s paintings that unlock these experiences for us. — Doug Meyer, Los Angeles Art Critic |

ANN LANDI

In studying other artists and cultures, and paying close heed to the world around her, Van Tuinen calls to mind the exhortation of Walt Whitman, another artist who was constantly striving to see the universe with fresh eyes: “You shall listen to all sides and filter them from your self.” |

|

Debra Van Tuinen’s works belong to traditions of landscape painting that might best be described as global. There are times when her dreamy panoramas evoke Asian art, especially in the use of gold leaf and lush jeweled color reminiscent of screen painting or even Japanese kimonos. At other points, she calls to mind mid-19th-century American Luminists like Martin Johnson Heade and Frederic Church, artists who ventured out into uncharted wilderness and captured the drama of a raw and untamed country. And a number of works evoke Claude Monet’s late series of the gardens and ponds at Giverny, a place where water, sky, and plant life dissolve into shimmering images of an insubstantial and ephemeral Eden.

Van Tuinen has been drawn to landscape for decades, at least since her undergraduate years as a student at Hope College in Holland, Michigan, on the shores of Lake Michigan. Later she studied at the University of Washington in Seattle, and now lives in Olympia, both cities accessible to the waters and wilderness of the Puget Sound. (Significantly, while pursuing her master’s degree, Van Tuinen owned a sailboat and spent a fair amount of time getting to know the shifting maritime moods firsthand.) Later the artist traveled to Japan, and the influence of that country’s traditions is still most immediately evident twenty years later in her “Paintings from the Garden” series, in which the precise outlines and dramatic contrasts call to mind the culture’s scroll paintings and byobu screens. But it is as a landscape painter that Van Tuinen has realized her greatest strengths and discovered her most inventive vocabulary. Her canvases from the mid-1990s show her working at conventional themes like the big scudding cloudscapes for which the Western skies are renowned. Yet even in shopworn subjects like sunrise and sunset the artist could turn convention on its head, choosing a long and dramatically narrow format in works like Island Sunrise (1997) and Last Glow (1997). These play with some of the tenets of Modernism—radical simplification, attention to the painting as an object, high-keyed color—without ever quite losing their identities as depictions of the natural world. It was the discovery of encaustic, though, that truly marked Van Tuinen’s maturity as an artist. The encaustic technique, which has been around at least since mummy portraits from 1st century B.C. Egyptian tombs, entails mixing pigments with hot wax and allows for a dense but translucent surface. Contemporary artists as diverse as Jasper Johns and Julian Schnabel have turned to encaustic to produce statements that run the gamut from coolly ironic to wildly expressionist. Looking for a way to get more texture into her work, Van Tuinen learned to use encaustic in printmaking about ten years ago, and in her hands, the medium can mimic the elusive realities of landscape—the insubstantial layering of clouds in the sky or the shifting density of water as light plays over the surface. Using oil stick has also provided a way of adding even more textural interest and translucency. Paintings from the last year, like Water Garden Reflections and Azure Transitions, mark some of Van Tuinen’s boldest ventures to date and show her moving in the direction of greater coloristic bravura and assured handling of her chosen medium. |

In recent years, the artist has played up the tension between representation and abstraction that animates her vision. In a painting like Transitions (2007), we ask ourselves if we are looking at a fiery sunset, a patch of sun-struck water, or an exceptionally compelling display of paint and wax on a flat surface. Often a cursory demarcation of colors will tell us if we’re looking down into a body of water or up at a roiling sky, but in many works the boundaries are not so clear, and the experience can be as mesmerizing as the uncertain weather of one of J.M.W. Turner’s storms at sea. These ambiguities become especially provocative in a work like Beach Meditation X (2007), where it’s not clear if the silvery sliver jutting from the upper right of the painting is a spit of land or a fragment of still water backed by mountains in the distance.

Over the course of her career, Van Tuinen has experimented with formats that similarly vary the impact and readings of her work. The strong vertical thrust of Canyon (2000), for instance, asks to be interpreted as something like a forest clearing between two stalwart tree trunks. Three Mighty Aires (2005) and Moonlight and Dusk (2009), both triptychs consisting of extremely attenuated vertical panels, invite comparisons with stately columns, but it is as through architecture were turned to evanescent pillars of paint. In almost all her work, Van Tuinen flirts with “objecthood” as the paintings make you aware of their presence and their purely physical attributes—these are, at the most rudimentary level, wax and pigment applied to wooden panels—but she never tips entirely away from the realm of the representational in the manner of, say, Donald Judd’s boxes or Frank Stella’s early series. At heart, she is still very much a romantic whose work has benefited from some of the rigors of Minimalism but looks back to earlier periods in art history. In studying other artists and cultures, and paying close heed to the world around her, Van Tuinen calls to mind the exhortation of Walt Whitman, another artist who was constantly striving to see the universe with fresh eyes: “You shall listen to all sides and filter them from your self.” — Ann Landi, Art Writer Ann Landi is a contributing editor of ARTnews and the author of The Schirmer Encyclopedia of Art.

|

John Spike

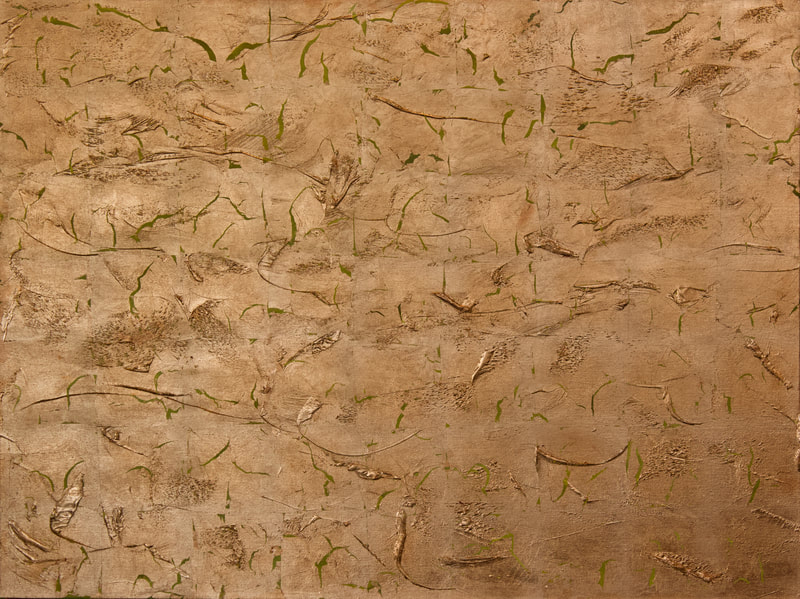

Debra’s ‘Old Growth/New Life’ is the most successful application of this technique I have ever seen. She has accomplished a miracle. |

|

Debra Van Tuinen is an artist who is making things more beautiful. Her work consists of delightful contemplations of twilight feel… The work evokes a tone ranging from Whistler to Rothko, and it acts to invite our contemplation and mediation. Gold leaf is evocative as twilight sun, as precious as gold. In general it makes the rest of the painting look poor. Debra’s ‘Old Growth/New Life’ is the most successful application of this technique I have ever seen. She has accomplished a miracle.

– John Spike, Critic and Director of the Florence Biennale John Spike is an American art historian, curator, and author, specializing in the Italian Renaissance and Baroque periods. He is also a prominent contemporary art critic and past director of the Florence Biennale. In 2007, Spike was appointed to the faculty of the Masters program in Sacred Art History jointly offered by the European University of Rome and the Pontifical Athenaeum, ‘Regina Apostolorum'. In 2011, Spike became a Distinguished Scholar in Residence at the College of William & Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia.

|

Old Growth/New Life, Encaustic

|

John Austin

This laissez-faire aesthetic dance impulse allows her to respond to her materials and to see what those materials can actually do instead of making them do anything. |

|

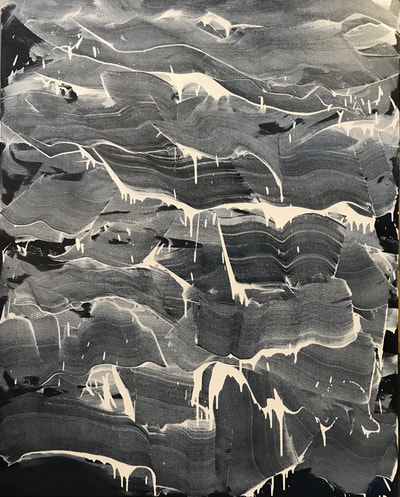

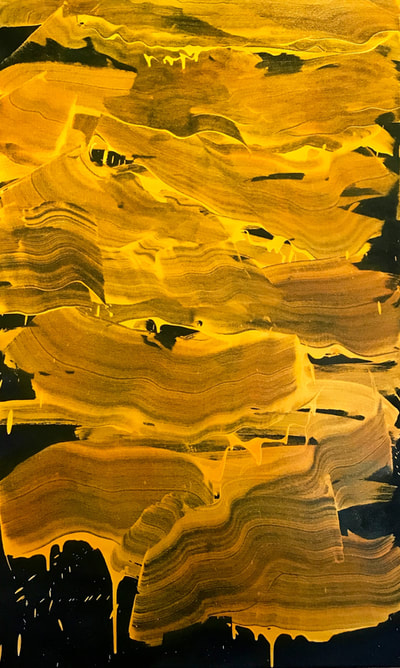

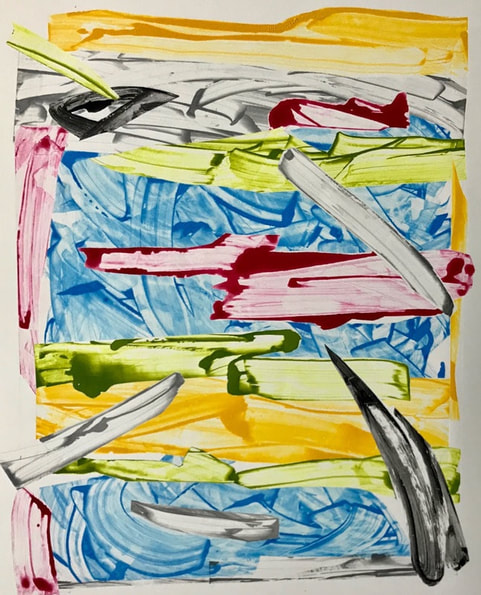

Debra Van Tuinen’s time-based paintings which are produced in a spirit of experimentation and sensitivity to the flow of gravity continues the tradition of Modernist painting and the color-field imagery. Her inspired conception points to both a repudiation of the virtuosity of execution while it celebrates great declarativeness, and the clarity of a holistic vision. A sense of purpose in Van Tuinen’s work might lie in its capacity to remind us as viewers that the concept of this type of expressive abstraction is not the conceived in and of itself; it is instead what it is said of it a posteriori, after the work is finished. The intuitive aspect of the artist’s artwork is paramount as its quality rests on that intuitive factor. The quality of the work also rests on the thing conceived as it is being conceived.

Debra Van Tuinen’s work is exceedingly time based: from the application of her materials, which include oil, encaustic and solve leaf, to the drying time of the materials on raw canvas and wood. This is process-painting of a certain kind as it is a type of Action Painting whose colorful skein-like patterns are both elegant and strident. The rivulets of paint which are allowed to flow across the pictorial plane and allowed to pool and eddy can have natural and organic sensations. |

A flow of water or clouds causes the colors and patterns to undulate with pulsating rhythms. Whispered sounds vibrate the tympanic membrane, inducing a shift in the air transforming its movements into electrical waves. In look at Van Tuinen’s sensitive works one could easily infer non-objective patterns which are representations of the tracks of subtle transferences of energy between gentle geologic forces and natural bodies.

Artist’s regulatory aesthetic impulse is to sensitively intuit where she wants t go without any prearrangement. This laissez-faire aesthetic dance impulse allows her to respond to her materials and to see what those materials can actually do instead of making them do anything. The result is an artist sharing with us what she has learned from paints intelligence and nature. Each of Van Tuinen’s work is good to look at, both in close and far away; they have subtle shadings and contrasts and project both an aura of calm and an inner light. John Austin, Manhattan writer |